Bassist Kelly Bryan became a member of Guaraldi's trio in the fall of 1967, during what was to become a transitional point in the jazz pianist's career.

|

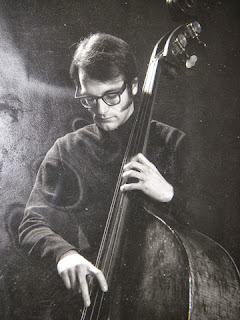

| Kelly Bryan in 1968: You gotta love the threads. (Sadly, no, he doesn't have any photos of his various gigs as a member of Guaraldi's trio. More's the pity!) |

In hindsight, we probably can’t blame him; jazz clubs had all but vanished by this point, replaced in the San Francisco area — as everywhere else — by folk and rock venues. Guaraldi undoubtedly regarded his first-gen electric keyboards as a means of remaining relevant. Perhaps to the dismay of his long-time fans, though, he experimented with these new toys on the fly, during his club appearances, rather than developing at least some technique in the privacy of his home studio.

The results often weren't pretty, but hey: It was the 1960s, and some listeners probably expected things to get way, way out during an extended jam.

Bryan was present at Ground Zero, during one such gig, and he remembers it well.

Anyway, Kelly cheerfully agreed to go into a bit more detail about his early days with Guaraldi, along with some general thoughts about the early days of electric instrumentation.

The rest of this entry, then, belongs to Kelly.

**********

In late January and early February of 1968, I played

for a week with Vince Guaraldi and John Rae at the Bear Valley Ski Resort, in

northern California. Vince had taken an interest in skiing and would spend all

day on the slopes. He must have done well, because he always made it back to

the lodge in time for dinner and the gig ... and all in one piece. I went

skiing a couple of times and took lessons from a pretty blond ski instructor.

By coincidence, she lived in Berkeley, too, so I got her number and dated her

for a while when we were both at home again.

It

might have been after the Bear Valley job that Vince said, "Well, Kel, now

we've played every kind of gig there is ... except a hanging.”

Vince

began to add an electric sound to his band around the time of a three-day

engagement we then had at El Matador, March. The band on those nights was a quartet

that included Bobby Natenson on drums, Bob Addison on electric guitar, and me

on electric bass. Vince brought his electric harpsichord and a large amplifier,

and set them up next to the acoustic piano. This was one of the first times he

tried out an electric keyboard in public.

One

result of rock music’s greater reach and popularity in the late 1960s was that

audiences became accustomed to bands, even jazz groups, playing at a higher

volume than had been the case just a few years earlier. It became fairly common

for jazz players to use a mike or a pickup — a transducer that captures mechanical vibrations —

on their pianos, guitars, string basses and other acoustic instruments.

In such

cases, the goal usually is to preserve the acoustic instrument’s sound while

making it a little louder, and achieving a good balance between all

instruments. Since acoustic instruments still “speak” the same way when miked,

the boost in acoustic volume level doesn’t necessarily mean that the musicians have

to change their playing techniques much, if at all.

Purely

electric instruments, however, could require a change in technique and

conception. In addition to playing the electric instrument itself, the musician

also must “play” the external amplifier and/or speaker, in order to achieve the

right sound at the right time. Some primarily acoustic instrumentalists had

problems for awhile, adapting or developing new playing techniques and styles

when first playing electric instruments.

|

| The interior of El Matador during its heyday, taken from the cover of owner Barnaby Conrad's memoir. |

During

the course of some songs, Vince switched back and forth between electric and

acoustic keyboards. This made for a difficult playing situation for the guitar

player and me, because the two keyboards — besides being set at different

volume levels — were very much out of tune with each other. The guitar and bass

simply couldn’t be in tune with both keyboards, during a given song. The music must

have sounded messy and pretty sour at times.

Musicians face numerous problems while trying to deliver an ideal sound:

a general inexperience with electronic and amplified sound; differences in

concept between band members; and a difficulty in hearing, because of the

room’s acoustic characteristics or an improper balance on stage. Any of these

problems can produce a common result: The band’s overall volume creeps up as

the individuals adjust their own levels, in order to hear themselves better.

The louder the volume gets, the more control over the sound and playing style

must be exercised by the musicians, if the end result is to avoid being messy

and unclear, sounding like a large serving of Mixed Fruit Salad.

Musicians who had played only acoustic instruments up to that time were

used to their range of volume being determined by a combination of their own style

and strength, and the instrument’s characteristics. Plugging an electric

instrument into a powerful amplifier opened up a whole new world for them. The

first time most players turned on their amps and cranked up the volume, they’d

be amazed at this new power, and would play too loudly. (Only rarely would

someone play too softly.) Everybody wanted to cut loose from the old instrumental

limitations, and try out the possibilities of the new electric axe ... and they

usually would, whether or not it suited the music.

Frank Zappa, guitarist and leader of The Mothers of Invention, once said

something to this effect: “Every pianist is jealous of guitar players, and

their ability to bend notes. Pianists can’t do that, so the first thing they do,

when sitting down at a synthesizer keyboard for the first time, is to play a

note and hit the pitch wheel. They just want to play a note that goes, Wheeeeeeeeeaaaahhhhhhhh.”

Power trumps musicality.

|

| Kelly again, this time circa 1967. He's pictured with his beloved Neuner and Hornsteiner Mittenwald, 1888 bass. Definitely something to treasure! |

A good sound man was — and is — an absolute necessity for bands

performing in larger venues; many bands bring along their own, as part of the

tour group. In smaller venues — nightclubs such as El Matador, at the time of

the Vince Guaraldi Quartet gig, for example — the band’s sound often is left to

one or more of the musicians’ best instincts and self-discipline. Individual musicians

using amplification and equalization (EQ) have more control over the volume and

sound of their own instruments than when a sound techie takes care of things;

as a result — for better or worse — the band’s volume and sound often are the

result of a group effort.

Bands playing any style of music must be aware of this chain reaction that

can lead to chaos, and how best to avoid it. Rock bands may have it a little

easier in this regard, because their music — 1960s and ’70s-style rock, at

least — tends to be harmonically and rhythmically more “open” sounding and less

complex than jazz often is. Jazz players have a tendency to play more notes and

more poly-rhythms than rock musicians. While this complexity might sound great

at an acoustic instrument level, when played on electric instruments — at

higher volume — the result can be muddy and inarticulate if the overall sound

picture isn’t well arranged and disciplined.

When jazz musicians played with rock musicians, the rockers often told

the jazz player to “simplify.”

After my El Matador gig with Vince in March 1968, I cycled out of

playing with him for awhile. I went to Africa in April and May, with the

University of California Jazz Quintet, on a U.S. State Department Jazz

Ambassadors tour. In the fall of that same year, I joined the Amici Della

Musica chamber symphony orchestra and stayed with them for 18 months. I didn’t

hear either of Vince’s gigs at Stern Grove or the 1968 Monterey Jazz Festival,

but the lukewarm-to-harsh reviews gave me the impression that the band must

have sounded something like it did during our El Matador sessions.

|

| A group shot of Grootna, from the back cover of their LP. You shouldn't have trouble finding Bryan. |

By that time, I knew quite a few of the local

rock and folk-rock musicians. Most knew of Vince and his music, and some knew

that I had played jazz with him. More than a few of the rockers — like most

club patrons, when they experienced Vince’s electric band — didn’t much care

for what they heard.

They wondered, sometimes out loud, “What the

hell is Vince doing there?”

The short answer to that rhetorical question

probably would be that the musicians were playing too many notes at high volume,

without enough arrangement or structure to define the song in a musical way.

Instead of creating space, they were filling

it all up.

I’m sure Vince’s longtime fans were happy when he eventually went back

to his acoustic piano style.

Disclaimer: The threads in the above photo were our, the University of California Jazz Quintet's, designated band wardrobe on our U.S. State Department Jazz Ambassadors, Africa 1968 tour. Pretty loud, but it was the 1960s.

ReplyDeleteKelly

Fantastic post, and many thanks to Kelly for providing such informative input -- both musically and historically. It was a wonderful window into that time and place and groove.

ReplyDeleteHaving heard a couple of Vince's electronic jams (I recall some improvised sets w/ Santana and Van Morrison doing the rounds of tape swapping forums in years past) it *is* hard to avoid the sense that he did sometimes succumb to the temptations of electric novelty at the expense of his own melodic forté. But while live venues may not have brought out his electronic best, I do still savor some of the magic he worked in the studio w/ his Fender Rhodes electric piano, especially on some of the 1970s Peanuts specials.

I agree with Duggadugdug, African Sleigh Ride has some great electric playing by Vince.

Delete-Darren