Sunday afternoon was way too much fun.

Constant Companion and I were among the full house present at Santa Rosa’s Luther Burbank Center for the Arts this past Sunday, October 9, for the world premiere of Playing for Peanuts: The Music of Vince Guaraldi.

Jazz pianist David Benoit, well regarded as the primo torchbearer for Guaraldi’s Peanuts legacy, along with his trio — Roberto Vally, bass; and Dan Schnelle, drums — were joined by the impressively large Santa Rosa Symphony. (Honestly, I’m not quite sure how all those musicians fit onto the comparatively small stage.) The Symphony was directed by Francesco Lecce-Chong, although Michael Berkowitz earned the spotlight as Principal Pops Conductor (beginning his final season with the Symphony).

Berkowitz was an ideal choice as conductor; he’s almost as animated as Bill Melendez’s TV special renditions of Charlie Brown and his friends.

This ambitious project has been a collaborative effort, for the past couple of years, between Benoit, Sean Mendelson and Jason Mendelson. Designing, developing and fine-tuning these new orchestrations of Guaraldi’s music — all arranged by Benoit — kept all three occupied while they were sequestered by Covid.

Their approach was quite clever: blending Guaraldi’s iconic themes — along with equally delightful, but lesser-known score cues — into themed “medleys.” The long-term goal is to take these new orchestrations “on the road,” and also to make them available for orchestral units across the United States (and anywhere else in the world). For the most part, the medley sequencing is immaterial, as is the decision on how many to include in a given performance by an ensemble of any size. Two, three or four medleys could serve as one-third of an orchestral performance; alternatively, many could be blended to make a two-hour Peanuts Guaraldi extravaganza.

Sunday’s Santa Rosa performance, at slightly more than an hour, came somewhere in the middle.

|

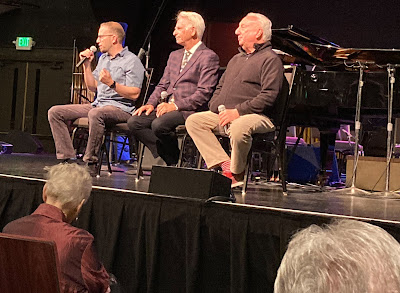

| From left, Sean Mendelson, David Benoit and Michael Berkowitz |

“Are you really not going to perform that?” she wailed.

The three men glanced at each other and chuckled. “Let’s see what happens,” Benoit finally said.

As Arthur Fiedler and John Williams often did when conducting the Boston Pops, Berkowitz chose to open each half with an unrelated orchestral piece. He impishly began the 3 p.m. performance with Johann Strauss II’s Perpetuum mobile (Musical Joke) for Orchestra, Opus 257. The piece is a roundelay of several minutes, with melodic elements that ultimately begin again … for as long as the conductor sees fit (or, in Berkowitz’s words, “until the audience begins to throw tomatoes”).

No doubt recognizing what this particular audience was present to hear, Berkowitz cut the orchestra off just as the second round began.

Benoit and his trio then took the stage for a delightfully structured Good Grief Medley, which smoothly blends “Oh, Good Grief,” “Frieda (With the Naturally Curly Hair)” and “Charlie Brown Theme,” with a return to “Oh, Good Grief” to conclude the arrangement.

Next up was a lively rendition of “Red Baron,” on its own. It was followed by a duet not included in the program: “Theme to Grace,” a portion of Guaraldi’s 1965 Jazz Mass for Grace Cathedral, nicely welded to “Happiness Theme.” (I also detected a few fleeting nods to “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” and wondered if anybody else noticed.)

Up next was another duet: a cheeky blend of “Peppermint Patty” and “Pebble Beach,” which grooved together so smoothly, that one was inclined to think Guaraldi would have wanted them performed that way.

The first half concluded with four waltzes collectively gathered as the You’re in Love, Charlie Brown Medley: “Rain, Rain, Go Away,” “Heartburn Waltz,” “Incumbent Waltz” and (of course) the title theme from You’re in Love, Charlie Brown. (By this point, scanning the audience revealed many patrons nodding in time to these 3/4 compositions.)

Following a 20-minute intermission, the lights dimmed anew, and the spotlight revealed that somebody had replaced Schnelle at the drum kit … but not just any “somebody.” It was none other than Maestro Berkowitz, who — clearly having had plenty of drumming experience — roared through Henry Mancini’s arrangement of Liam Sternberg’s “Walk Like an Egyptian.”

Berkowitz generously returned the drum sticks to Schnelle, and then the trio — absent the orchestra — dug into “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” with Benoit smiling as he began a gentle keyboard rendition of Guaraldi’s Grammy Award-winning classic. But this was mere preamble; Schnelle kicked up the tempo, and Benoit delivered a furious keyboard bridge, and then handed things off to Vally, who practically made his bass talk.

Benoit’s association with the Peanuts franchise sometimes brands him as an “easy listening” jazz guy; this lengthy rendition on “Fate” immediately disabused that notion. These three guys whaled.

Possibly determined to prove that they were equally capable of delivering some excitement, the orchestra then rose to the challenge with an equally vibrant handling of “Air Music (aka Surfin’ Snoopy).” It’s one of Guaraldi’s most rockin’ Peanuts themes (and Benoit frequently opens with it, during his annual Christmas shows).

“Graveyard Theme” and “Great Pumpkin Waltz” followed, blended as the aptly titled Pumpkin Medley. The subsequent Woodstock’s Medley gathered four tunes: “Woodstock’s Wake-Up,” “Little Birdie” — with some sassy orchestral horns compensating for the absent vocal — “Woodstock’s Dream” and “Thanksgiving Theme.”

Having acknowledged both Halloween and Thanksgiving, the program logically concluded with a soulful Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown Medley. The rockin’ finger-snapping “Christmas Is Coming” segued to a lyrical “Skating,” with Benoit effortlessly handling the all-important keyboard cascade; this segued to poignant readings of “What Child Is This,” “O Tannenbaum” and “Christmas Time Is Here.”

|

| Pianist David Benoit waves a greeting, as the World-Famous Beagle joins the musicians on stage. |

The world-famous beagle strutted across the stage, positioned himself alongside Benoit, and grooved (mostly) in time, as the trio and orchestral delivered a lengthy rendition of this most famous Peanuts theme. When Benoit finally leaped up, apparently to signal the end, a second standing ovation prompted him to sit down again … at which point he launched into a “One more time!” encore of “Linus and Lucy,” but, um, in a rather unusual key.

Nobody seemed to mind; when he, his trio and the orchestra finally finished and took their bows, all received a third standing ovation.

As the patrons departed, amid much laughter and merriment, it was obvious that Benoit, Sean and Jason Mendelson had created a sure-fire audience pleaser.

Granted, a symphony — despite its best efforts — can’t swing like a jazz combo; it’s also true that Guaraldi’s gentler themes lend themselves better to orchestral arrangements, than his high-intensity rockers.

Even so, Playing for Peanuts is an impressive marriage of jazz and classical. And — most important — it’ll definitely encourage folks to more fully investigate Guaraldi’s oeuvre.

And that’s what it’s all about, right?

No comments:

Post a Comment