In that way, I'm grateful to a good friend for calling my attention to a delightful online profile of Dogpaw Carillo, the sort of cheerful, colorful figure who typifies San Francisco's still-quite-lively counter-culture vibe. Dogpaw — and that's how he prefers to be called — is the star of this engaging and informative article by Viktorija Rinkevičiūtė, which she wrote during her post-graduate stint as a master's student in media, journalism and globalization, while at UC Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism. She subsequently returned to Lithuania, where she maintains an engaging blog and looks back fondly on the time she spent in Northern California.

As you'll discover, reading Viktorija's charming piece, Dogpaw spent part of his childhood living directly adjacent to the Treat Avenue headquarters of Fantasy Records. He grew up in a house at 841 Treat; Fantasy was next door, at 855 Treat.

(A quick sidebar: We have become conditioned to assume — thanks in part to a Vince Guaraldi composition — that Fantasy's most famous early home was on Treat Street. But Guaraldi's tune isn't the only source; this slight error has been promulgated by scores of musicians who refer to the good ol' days, when "Fantasy was on Treat Street." Many of them are quoted saying as much in my book. The lapse is understandable; "Treat Street" rolls more swiftly off the tongue, and the rhyme is hard to resist. But it's a mistake nonetheless: Although San Francisco does possess a tiny Treat Street, it's nowhere near the Mission District locale where Fantasy Records made its home ... on Treat Avenue.)

Aside from being absorbed by Dogpaw's childhood memories, I was drawn to the several times he mentioned Guaraldi. Viktorija had no reason to pursue these references to Dr. Funk, since her story focused more generally on Dogpaw, then and now. But I sensed that he'd have more to say about Guaraldi, and so I contacted Viktorija. She kindly shared Dogpaw's contact information, and she also sent along several additional photos that she hadn't used in her article.

I found Dogpaw just as amiable — just as eager to chat about his Treat Avenue days — as I would have expected. And he did, indeed, have a great deal more to share about Guaraldi and Fantasy.

(I've tried to avoid too much overlap with the information in Viktorija's article, although some basic details are necessary.)

|

| Dogpaw examines the exterior of 855 Treat Avenue, the once-upon-a-time home of Fantasy Records, and now headquarters of the San Francisco Mime Troupe. (Photo by Viktorija Rinkevičiūtė) |

"Fantasy was literally right over the fence," Dogpaw recalls. "They shared the property with a lumberyard; this guy would come in maybe once in a blue moon, and chop and saw some wood, and then take off. His buzz-saw was right next to the studio! But they must've worked it out, because he never made noise when Max [Weiss] wanted to record something.

"At first, I thought the place next door might be a radio station, because you'd see instruments being loaded off vehicles, and going in, and later coming back out again, and all these radio-looking people. That was the vibe, so we kids knew it had something to do with music. Initially, we all thought that every neighborhood had one of these places, like every neighborhood had a playground or a library. This was just normal to us, having a studio on the block.

"But of course it wasn't normal. Growing up on Treat was very, very special."

Dogpaw generally heard music wafting from Fantasy from noon onward, and he later learned that these were rehearsal sessions.

"They'd leave the studio door open from time to time, especially in the summer," he laughs, "because it was a real sweatbox back there. But they'd close the door during recording sessions."

Guaraldi was a frequent presence.

"Vince spent a lot of time there, usually hanging out with Max. The feeling was, it was the place to be. And Vince was cool; he was, like, this mustache. That's how we knew him. We kids were allowed to go pretty much everywhere within the building, and we'd see Vince in the office, talking to Max. I used to go to the store for them, while Vince and Max were sitting there, chatting over coffee or lunch.

"Vince was like a regular guy; you never got a sense that he thought he was famous. It was more like he felt that he was where he was supposed to be. You'd see him walking down the street, and you knew that he was a part of you. He didn't behave like a superstar. He wasn't like the Beatles, in the sense of artists being separated from the community. Vince was one of us, like your uncle: part of the neighborhood. He was on our team; we understood him ... a down-to-earth, eye-level guy. He'd talk to us kids about anything, and was totally zen: 'I'm cool, you're cool; let's rock a little!' You always got a sense that he lived in the moment.

"He was great with us kids. He had a yo-yo, and I remember the tricks he did. He was captivating, and we'd ask him to do them again and again."

What, I wondered, did he look like?

"He'd wear cords, turtlenecks and sports coats ... nothing crazy, not like a hippie. Although he did have long hair at one point; everybody did, back then."

Despite the passage of half a century, Dogpaw's memories remain vivid. I can picture him standing in the home that Viktorija described so well, surrounded by concert posters and stacks of LPs and CDs.

I barely had to prompt him with questions, and every so often the general anecdotes were punctuated by a specific incident that I could tie directly to a seminal moment in Guaraldi's career.

For example:

"I remember one time, this was when I was younger, that the studio had a ton of Peanuts stuff on the first floor: all these small paper posters of Charlie Brown and the others. Just stacks and stacks of this stuff!"

That would have been in late 1964, a month or so prior to the mid-December release of Guaraldi's Jazz Impressions of A Boy Named Charlie Brown album. As recounted in my book, Lee Mendelson recalled spending an afternoon at Fantasy, helping Max, Saul Zaentz and other studio folks stuff Charles Schulz's 8-by-10 mini-posters into the luxurious gatefold album cover that Fantasy had produced for the first printing of that LP (at the point when it still was assumed that Mendelson's A Boy Named Charlie Brown documentary would be aired on television ... which, sadly, never happened).

I asked if Dogpaw had ever seen Guaraldi and his band lay down some tracks.

"Oh, yeah; that was cool. We could see them through the glass. The studio had these sound walls, so you couldn't see everybody unless you moved around. You got a sense that they were flying a plane together, and the musicians would look over toward the window, where the sound engineer was, and where Max was wearing his headphones."

Mostly, though, Dogpaw remembered Guaraldi from more casual encounters.

"Max had a black Lab and a Rhodesian Ridgeback, the latter named Nofka. She had puppies, and one went to Vince ... I think he named it Blanche. Vince would bring his dog over, and it would play with Max's dogs, and Vince would play catch with them. The dogs would run all around the lumberyard, and we kids would play with them.

"At other times, Vince talked to Max about wanting to have an environment where he could play jazz for kids ... not like nightclubs, with everybody smoking and drinking, and people occasionally acting stupid. Vince wanted a place for kids to hear jazz, so they'd want to grow up and play it.

"Jazz always had an appeal to kids. Think about the big bands and orchestras that did the Warner Brothers cartoon music in the 1940s and '50s; that was awesome music. We'd hear that music when the cartoons showed on TV, in the 1960s; we were so spoiled.

"Vince was the same way."

[Dogpaw undoubtedly is referring to the wonderful Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies themes made famous by Warners composer/arranger Carl Stalling, who borrowed numerous tunes from eclectic jazz genius Raymond Scott.]

Dogpaw doesn't merely enjoy jazz and music in general; he regards it with the reverence normally associated with religious belief.

"Playing live music," he insists, "is about the closest thing we have to an actual democracy."

Guaraldi wasn't the only regular visitor at Fantasy, of course, and Dogpaw recalls numerous other comings and goings.

"The place always had music, and the diversity of artists was staggering. I remember when Bola Sete came by; that was probably the first time I'd ever heard Brazilian music being played by somebody actually from Brazil. Bola and Vince together were amazing, the way they could make such beautiful music.

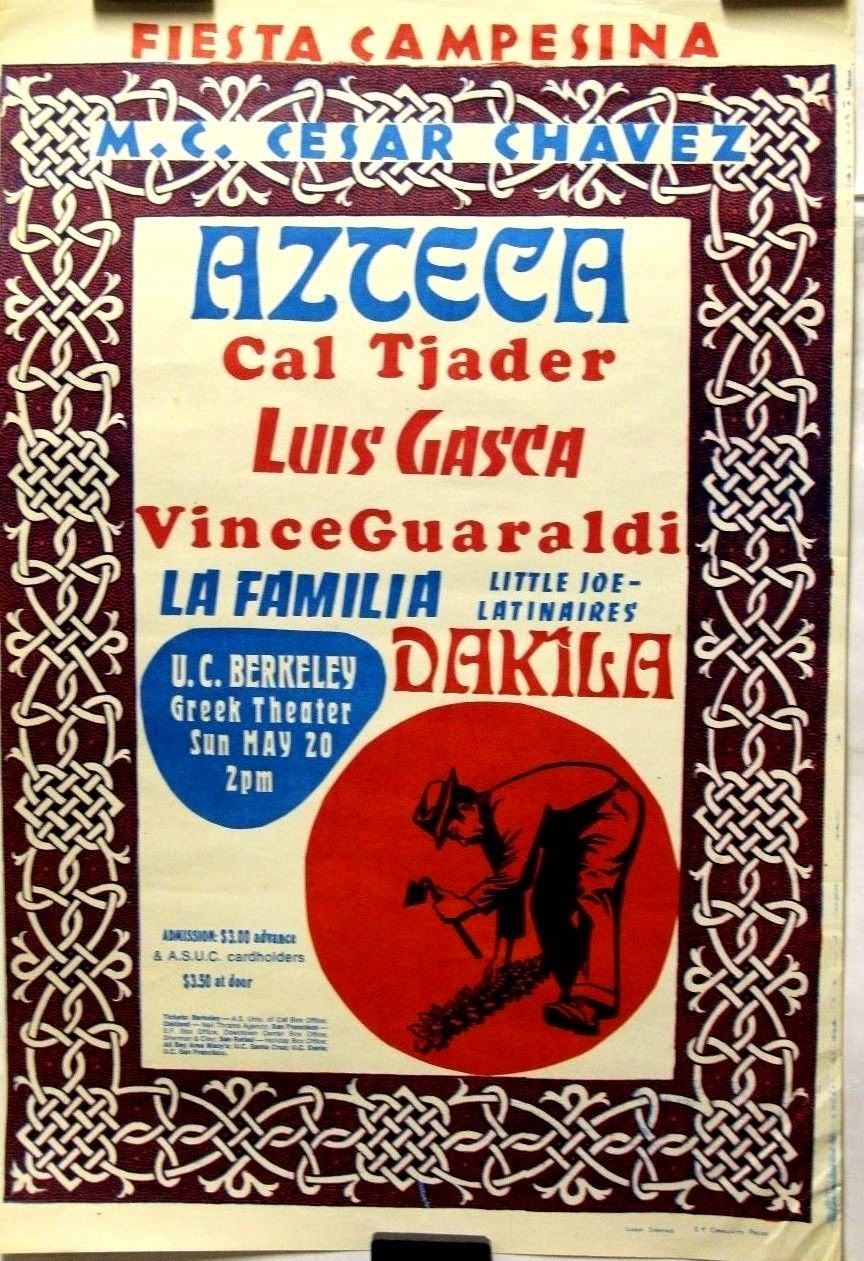

"I never saw them perform together, although I did see Bola play with Cal Tjader once, in San Jose. It was one of the Fiesta Campesina events, which also had Dolores Huerta on the bill. Those were amazing shows, that brought all the little music tribes together. That just doesn't happen any more."

Which begged the obvious question: Did Dogpaw ever see Guaraldi perform live?

"Only once, at another Fiesta Campesina event, in 1973. So much variety ... each band was so different. César Chávez would show up, as the master of ceremonies. He'd talk about the United Farm Workers, and the grape strike, and so on. He'd introduce the bands, and Vince was one of them. I remember he did a mix: some of the traditional pieces that people expected him to play — "Cast Your Fate to the Wind," "Linus and Lucy" and some of the Christmas pieces, even though it wasn't Christmas! — and he did some newer things, and sang some stuff. He also did some Latin jazz, stuff that made you think of Tito Puente and Eddie Palmieri. It was a nice set, where he showed all these different colors and textures.

"I often wonder if anybody recorded that show."

[As do we all...!]

The passing reference to the holidays prompted a bit of reflection.

"In our American culture, winter is the only season that has its own music. If you play Christmas music in July, people look at you funny.

"And Vince has become part of the iconic American Christmas, like the Thanksgiving Day parade. He's there every year. His music was built to last.

"Vince deserves to be profiled on something like PBS' American Masters. He's still this unsung guy, and every year, around Christmas, a whole new crop of kids get a chance to hear his music. That's pretty unique; I can't think of another artist who's celebrated annually that way. And I watch the Christmas show every year, right along with all those kids.

"I own the DVD, but that's not the same. There's something special about watching it during that annual broadcast."

Close to 90 minutes had passed, and Dogpaw finally had wound down, unlike any of the dozens of clocks also mentioned in Viktorija's article. The pauses between anecdotes had grown longer than the anecdotes themselves. I thanked him for his time, sensing — even through the distance of telephone lines — the ready, radiant smile captured in several of Viktorija's photos.

And I wished that I had been a kid like Dogpaw, growing up in a neighborhood where it seemed utterly ordinary to live alongside a recording studio.

15 comments:

Magical recollections of an unrepeatable time; They're really evocative of that place and vibe. Thanks for taking the time to plug your online readership into Dogpaw's memory. The open-door accessibility of the Fantasy operation that he describes is unexpected and beguiling -- where's my time machine when I need it? :-)

And I couldn't agree more about an "American Masters" profile on Vince. PBS should get busy before all of the first-hand witnesses to his musical career are gone.

What a great post! Thanks!

I'm going to have to pull out my copy of "Vince Guaraldi at the Piano" to look for such details, but I'm now suddenly curious to know whether and which Vince albums were recorded at the 855 Treat Ave. address...

As the son of Sol Weiss (Max was my Uncle) I wish *I* had lived closer to the studio (we lived in Marin). I remember some good times there but mostly on weekends, when there weren't people recording.

Even as an occasional weekend visitor, you must've seen -- and heard! -- some great stuff. Please get in touch; I'd love to find out what you recall about some of those memories.

Just doing a bit of research into the record production career of Max Weiss. I was tipped off about an obscure early '70s label, Rebosak, being one of his later ventures. The artists presumably still used the "Treat Street" studio to cut several 45 sides and it sounds like the open-door policy still stood... artists and musicians of every genre, indeed beyond genre, stopping in to cut demos or just rehearse. I think it would be interesting to catalogue and discuss Max's continued dabbling in record production in the wake of his heyday at Fantasy.

Thank you Derrick for writing such an accurate account of my years as a child growing up next door to the house of the magicians, also known as Fantasy/Galaxy Records. It certainly makes my heart swell knowing that people from all over the world can still feel this man's vision, the way I did so long ago. He was part of a precious, and fertile musical habitat called the west. And, I am elated to hear that his musical presence has at long last, a place at the Smithsonian Institute. I'm very happy that our time spent on this interview yielded such an insightful painting of lost moments in Vince's journey. I'm very honored to have been part of this very wonderful retelling of a story that will help keep the memory of my friend alive for a long time to come. He is forever in my thoughts, and I miss him very much. Thanks again, Derrick Bang. Your friend, Dogpaw Carrillo

Goodness, the thanks are equal. Great interviews come from enthusiastic folks with fascinating stories to tell, and I'm honored that you were willing to share yours. I'm much obliged!

Hey, Mr.A, your brother here! Even though I got to come to the plant I don't remember any recordings taking place. Strange. I do remember playing in the lumber rack like a big jungle jim. And playing in those record racks, I believe there is a picture of Vince curled up in one of them on an album cover.

Mr. K

I grew up IN the studio and it was a weird and wonderful place. My father Sol Weiss was interested in all sorts of tech and also had a color photo studio in there. I'll never forget the time they signed Joan Baez when she was 17 and then had to destroy all the records. After Uncle Max (Weiss) hacked through a box with a machete, my brother Chris and I got to fling the records like Frisbees into the back lot. Good times...

Alan, you must have an incredible wealth of other memories. If any of them concern Vince, I'd love to chat. Please get in touch via my email address above!

Great interview! I'm so glad I found this page. Max Weiss sounds like an interesting guy. If Max wrote a book I would purchase it. And the history of Fantasy records would make a terrific documentary.

Derrick, I cannot begin to tell you how much I appreciate your contributions to keeping musical history alive, especially jazz, more specifically Guaraldi. And now the history of SF Fantasy, a studio where I recorded a couple of my projects in Berkeley, peaks my interest (side note: I designed the first website redesign for Fantasy as a trade for studio time, around 2002?) But I digress: how awesome to have this great interview from a first-person perspective! And then to read comments above from the Weiss’ kids/nephews! Thank you for making my day/week/month with this interview!

Hey there son of Sol Weiss!

I hope you're doing well at this special time of the year. I want to wish you and your family much love and gratitude for playing such an inspiring role during my childhood. These are precious memories of 855 Treat St. that I've carry with me forever! Today it's the home of the San Francisco Mime Troupe. I oftentimes remind some of the young interns there about the history of the actual recording studio which now serves as the woodshop for the set builders now. Yeah, art keeps going! It was a complete joy bringing these memories out of the dustbin. Anyway, I just want to wish you a safe, warm, and wonderful Christmas finally after all these years! Be well my friend!

I'm a metaphorical "Son of Sol" at best, but I appreciate the spirit, and it's always great to hear from you. Best holiday wishes to you, as well ... and may the season be filled with plenty of great music!

Post a Comment