As the years have passed, and this blog’s status has risen via Google searches, I’ve occasionally heard from first-time visitors eager to share their long-ago “Guaraldi encounters.”

This is a good one, courtesy of a lovely woman named Peggy Tillman, who — way back in the day — unexpectedly found herself seated alongside Guaraldi, on his piano bench.

But that’s getting ahead of things.

Sonoma State College — in Rohnert Park, California, just a few minutes south of Santa Rosa — opened to 274 students in the fall of 1961. Because the campus still was far from completed, many of the classrooms and other key activities took place in leased buildings within the city.

Peggy transferred into Sonoma State in the fall of 1963, her sophomore year; she remembers the still-gestating state of affairs. “Our ‘library’ was built as a grocery store,” she laughs, “and after we moved out, a few years later, it became a grocery store.”

The student body, still quite modest, included a disproportionately large percentage of adults: either working folks looking to secure credits for a long-delayed graduation, or retired individuals with the time to enhance their knowledge. “The joke,” Peggy recalls, “was that the average age of the student body was higher than the average age of the faculty. When school administrators sought input on the creation of a school mascot or symbol, somebody suggested a rocking chair.”

Jokes aside, these “returning students” were a challenge. “They were tough competition: far in advance of us, because they had life skills, better study habits, and often were taking only one or two classes, whereas we younger students were taking a full load.”

Peggy entered as an education major, with an eye toward teaching, but — as luck would have it — California changed its academic requirements that year, mandating a fifth year of post-graduation instruction in order to obtain a teaching degree. Preferring to graduate in the planned four years, Peggy switched majors and entered the psychology department.

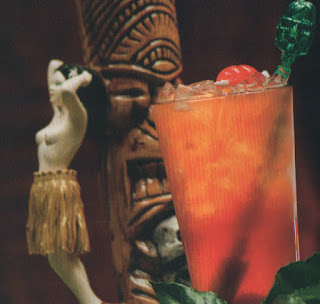

Toward the end of her junior year, the campus Concert and Lectures Committee booked the Guaraldi/Bola Sete Quartet for a performance on April 5, 1965. Since Sonoma State did not yet have a performance hall, the gig was scheduled into the nearby Cotati Veterans Memorial Auditorium. Admission was free to students, and $2 for the general public.

By this point, Peggy had become one of the three people who made up the college’s fledgling audio/visual department; thanks to her experience as campus photographer during her high school career, she stepped into that same role for Sonoma State. One of her psychology department professors, Dr. Frank Siroky, was doing research on the body postures of people, as they listened to music; he hired Peggy to take pictures of the audience during the upcoming Guaraldi/Sete concert.

(Ah, such innocent times. It’s an intriguing research premise, to be sure, but it’d never fly in today’s hyper-vigilant era of privacy concerns.)