Commentary, discussions and random thoughts about San Francisco-born jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi, beloved by many — including those who recognize his music, but not his name — and affectionately known as Dr. Funk

Monday, May 5, 2025

Wheels within wheels!

Wednesday, April 30, 2025

From album to manuscript page

I’ve played piano since childhood, although I never rose beyond the level necessary to perform for local community theater productions. Even so, I’ve continued to dabble, and of course have purchased every Guaraldi songbook or sheet music single that came to my attention.

I started young. In the late '60s and early ’70s, Pointer Publications, a division of what then was Hal Leonard/Pointer Publications, put out a series of easy piano books — the Peanuts Keyboard Fun series — which were adapted from the early TV specials. The books typically contained 32 pages, and the two center pages featured full-color illustrations from the show in question. The musical contents tended to cross over from book to book; in other words, if you had two books, they’d have some of the same songs, and some unique to each book.

The books were $2.95 each, and included the following volumes:

• A Charlie Brown Christmas

• Charlie Brown's All Stars

• It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown

• You’re in Love, Charlie Brown

• He’s Your Dog, Charlie Brown

• It Was a Short Summer, Charlie Brown

My library has grown substantially since then, and recent years have been a true Renaissance. As a sidebar to all the recent Peanuts soundtrack albums released by Lee Mendelson Film Productions, Sean and Jason Mendelson also worked with Hal Leonard LLC, a music publishing and distribution company that dates back to 1947, to publish many cues and songs never before released in sheet music format, as I covered in an earlier post.

I recently realized, as a result of my ongoing collaborations with Sean and Jason, that I had an “in” to answer a question that has long intrigued me:

How does a song get transcribed? What’s the process?

Sean put me in touch with Ben Culli, Hal Leonard’s Vice President of Editorial and Production, who turned me over to keyboard publications editor Mark Carlstein. He and I had a delightful chat a few weeks ago, and all my questions were answered.

The first one was obvious: Are transcribers musicians themselves?

“Yes,” Mark replied, “that’s absolutely imperative.”

So ... when starting work on a new tune, Mark — a pianist himself — handles the initial steps.

“The first thing is to get a good recording that’s indicative of the song. If I’m looking at Bill Evans, he might have recorded a given tune half a dozen times, and I’d want one that best represents him playing that music.”

Next: “catalogue” the tune.

“Every song has a road map. In the same way you’d follow a route, to get from A to B, a given song will last a certain number of bars, in a certain time signature, and in a certain key signature. Some sections may repeat, or not; typically in jazz, you don’t have exact repeated sections, as often is the case in pop music.

“I then send the representative tune to one of our transcribers, along with my road map; they listen to it, and write down everything they hear. All the parts are important. If words are part of the song, those words also must be transcribed. All of the melody’s rhythms must be notated precisely.

“What you look at, when you sit down to play something from a songbook, is a finished document that the transcriber built from the ground up.”

In the case of a Guaraldi trio composition, the transcriber pays attention to both the keyboard work, and the bass, to pick up the latter’s supplementary notes.

“The trio musicians will be playing the same harmonies and chords, but not necessarily the same notes. (We always ignore the drums, because that’s a non-tonal portion of the recording.)”

Vocalists, often backed by larger ensembles, are trickier.

“Take a Taylor Swift recording. It’ll have a bass line, a guitar player, a piano player, perhaps another keyboard player, perhaps a secondary guitar player, the vocals and the words. All of that must be distilled into something that can be played — say, in the case of a pianist — by one person with two hands. As a result, a lot of compromises are involved, and it’s necessary to focus on the essence of the song.

“How much of what the bass player does should be included? Some of it can’t be played by a pianist, and it’ll never be in the same octave, because what the bassist plays sounds too low on a piano keyboard; the two hands must be kept closer together.

“You also can’t play a busy guitar part at the same time you’re playing the melody and bass line.

“Everything can’t be included, and that’s the biggest challenge for our transcribers who handle vocals, because we always include the melody in the right hand, and everything else must be inserted around that. Our transcribers therefore start first and foremost with the melody, because it’s imperative that it be presented in a way that can be played by that one person with two hands.”

Are vocal pieces easier than instrumentals?

“Yes, because you’re looking primarily at the melody and bass line; far fewer parts must be coordinated into a single playable score.

“Alternatively, right now I’m working with one of our best transcribers on a jazz piano Omnibook, which includes classic recordings by Herbie Hancock, Oscar Peterson and everybody else you’d immediately recognize. But few of the pieces are solo piano; most involve at least bass and drums, and perhaps one or two horns. In such cases, you can’t include every single thing that every instrument plays, but all of the piano stuff is transcribed precisely — everything exactly as was played by that particular artist, on that particular recording — and the other instruments go onto other staves. One pianist can’t possibly play everything, but an Omnibook like this serves as a reference of sorts.”

What determines the necessary skill level required to play the result?

“That gets into arrangements. ‘Exact transcription’ means note for note, and the result can be quite complex and extremely difficult to play, because we’re talking about musicians who have extraordinary skills. If you’ve tried to play anything by Oscar Peterson, you know right away; it’s next to impossible. But something like the Omnibook isn’t what Hal Leonard does most. The bulk of what Hal Leonard does, is to take songs that people know, and to present them in different ways: different grade and skill levels.

“Looking at just piano, we have at least a dozen different skill series, and of course we also have stuff for clarinet, violin and all sorts of other instruments. So, one person might do the initial transcription, and then several other people will handle the various arrangements.”

Why are some transcriptions in a key that differs from the original performance?

“We try to present things with no more than four sharps, or four flats. When we transcribe and arrange what we call ‘sheet music’ for the consumer, 1) the melody must be in the piano, so it can be played; and 2) it can only be reasonably difficult, at worst.

“We’re super-conscious of keeping things at an average consumer’s ability level, so that almost anybody can pick up that sheet music and make use of it, and enjoy it. Part of that involves avoiding complicated key signatures.

“A lot of jazz and pop musicians like keys that have five and six flats, because it works well under their hands, like certain sharp keys work better for guitar players.

“But the rest of us,” Mark added, with a chuckle, “don’t like seven sharps or seven flats.”

Indeed, some books are deliberately signature-simple.

“One of our most popular series is My First Fake Book, and every song is in the key of C major. We make it easy for the consumer, and of course you can transpose a song into any key you want.”

During my childhood, almost everybody I knew had a piano in their home, as also was the case in ours. These days, though, one sees very few pianos in homes. Has that affected sales of songbooks and sheet music singles?

“No, because all sorts of electronic keyboards are available these days; they’re less expensive and portable. The nature of the product has changed, because so much is available online; a lot of people download sheet music, as opposed to walking into a store and pulling something off a rack.”

Mark laughed at my next comment: One of my ongoing pet peeves has been the annoyance of square-bound songbooks. I’ve long felt that every songbook should be spiral-bound ... but I guessed (accurately) that must be too expensive.

“As far as I’m concerned, having the book stay open, while on the music rack, is the most important thing. So for Hal Leonard’s jazz piano solos series, at 96 pages, we switched the binding to what we call ‘lay-flat binding,’ so you can open the book anywhere, and it stays open and doesn’t split the spine.

“As it happens, the Guaraldi volume in that series is one of my favorites.”

That book is pictured at left; check it out here. Click on "closer look," below the photo, to see sample pages from "A Day in the Life of a Fool (Manha de Carnival)," "Great Pumpkin Waltz" and "Skating."

In the case of the Guaraldi cues and themes recently released in The Peanuts Piano Collection, Ben then explained that one final step was involved: “Sean reviewed the transcriptions prior to release, and offered a few very small suggestions and tweaks.”

And there you have it.

Many thanks to Mark and Ben, for fully satisfying my curiosity.

Monday, March 24, 2025

A couple of terrific reunions

Two new YouTube goodies absolutely deserve your attention.

The first is the most recent episode of Heath Holland’s Cereal at Midnight podcast, an ongoing program that he cheerfully describes as “the culmination of an entire lifetime of nerdy pursuits.”

That’s a fair descriptor of many episodes, but I wouldn’t call this one nerdy.

With an assist from Jason and Sean Mendelson, and timed to the upcoming release of the soundtrack for It’s the Easter Beagle, Charlie Brown, Heath gathered three veteran jazzmen — drummers Mike Clark (perhaps best known for working with Herbie Hancock) and Eliot Zigmund (famously with Bill Evans), and bassist Seward McCain (Mose Alison, Cleo Lane and others) — for a group Zoom session, to discuss their long-ago stints as members of Vince Guaraldi’s various combos.

The hour-long result is a wealth of reminiscences, anecdotes and some observations about jazz itself. Aside from their times with Guaraldi, topics include the respective jazz scenes in New York and San Francisco — and the often notorious divide between East and West Coast jazz — and how exposure to classical music (!) influenced their careers.

It's also fun to see how these three guys genuinely enjoy the camaraderie. Goodness, Seward and Eliot hadn’t seen or spoken to each other in decades.

I don’t want to spoil the viewing experience, but — as I furiously jotted notes — a few nuggets are worth mentioning.

|

| Seward McCain and Vince Guaraldi at Butterfield's circa 1974-76 |

Mike’s comment is almost unbelievable, because he didn’t realize he was making music for a television special: “[Vince] would call and say we’d be in the studio that day, no clue what we’d be playing. I don’t recall him ever saying anything about Charlie Brown. He’d just say, Okay, give me a groove like this, or give me 28 seconds of this, and I had no idea what it was for. He’d play like Wynton Kelly, and we’d just swing all night. And then this stuff aired on TV for years, before I even knew I was on it!”

Eliot credits his time in Vince’s trio with getting him the gig with Bill Evans; Mike recalls being recommended to Guaraldi by saxophonist Vince Denham, and fondly recalls the “great jams” at San Francisco’s Pierce Street Annex. All three men still perform; Eliot, soon to turn 80, wittily observes that “Drummers need to stay in good shape. I don’t dig carrying the drums, but I love playing them.”

And here’s something I never knew before: Mike mentions playing classical music with Vince at San Francisco’s Glide Memorial Church. (It’s worth noting that chanteuse Faith Winthrop, who was backed by Guaraldi’s early hungry i trio, founded that church’s community gospel group.)

Seriously, Mike? When? When?!?

All three still remember Vince fondly.

“Vince was fun to be around,” Eliot says, wistfully, “and he loved to swing.”

“Vince played with rhythm, and he was in the groove,” Seward adds. “His notes were a lot of fun. Vince laid it down.”

“He had a dirty beat,” Mike concurs. “He could play New York style. And he could play two-handed boogie-woogie like nobody else.”

Referencing the fact that Guaraldi can be heard saying “Cue 1!” at the top of the first track on the Easter Beagle album, Mike adds, “As soon as I heard his voice, it hit me in the heart, and made me think how much I loved that guy.”

Amen to that.

********

The aforementioned album concludes with a truly special bonus track, recorded in 2021 at the same San Francisco studio where this soundtrack was laid down half a century ago: a brand-new “Woodstock Medley” — blending “Woodstock’s Wake-Up,” “Little Birdie,” “Woodstock’s Dream” and “Thanksgiving Theme” — by the trio of Seward, Mike and pianist David Benoit. It’s a fabulous performance, running just shy of 7 minutes.

I’ve known, pretty much since the medley was laid down, that Sean and Jason also filmed it ... and I’ve yearned, for almost four years, to see that footage.

Well, now everybody can watch it, in Sean’s marvelous music video, which he co-produced with Jason, and co-edited with Palmer Mendelson. The film is a captivating document of the studio performance, interspersed with brief “talking head” commentaries by the three musicians.

The nicest, heart-tugging touch: a final shot of Lee Mendelson, wielding a clapboard, while standing in front of Peanuts memorabilia that includes an impressively huge stuffed Snoopy.

Honesty, guys; clap yourselves on the back. This is a treasure!

Monday, November 4, 2024

Heart and soul!

Thursday, August 29, 2024

This Election features a different McCain!

Heath Holland, host of the pop-culture podcast Cereal at Midnight, has been delivering marvelously passionate shows about Lee Mendelson Film Productions’ recent, never-been-seen-before releases of Guaraldi’s scores for the vintage Peanuts TV specials, always with the equally enthusiastic participation of Sean and Jason Mendelson.

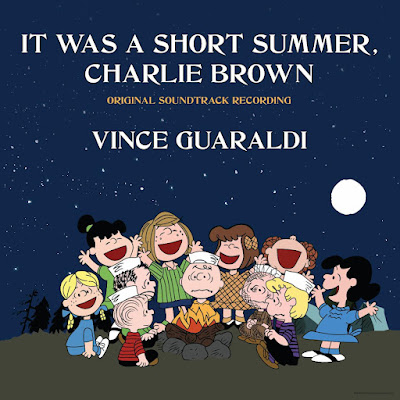

Check out the previous shows devoted to A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving and It Was a Short Summer, Charlie Brown (which also earned a second show).

Holland’s just-posted coverage of You’re Not Elected, Charlie Brown finds the aforementioned individuals similarly excited — and excitable — but it’s also extra-special for an additional reason. Bassist Seward McCain, a former Guaraldi sideman, also participates in this super-sized episode; he’s on camera for most of the first half-hour. His memories, anecdotes and commentary are wonderful.

I don’t want to spoil the fun to be had while watching the entire show, but I couldn’t help extracting some of Seward’s choice remarks.

In his voice, then:

It was interesting to hear these [album] cuts, because it reminded me of how Vince worked. We would show up at the studio — usually a two-day session — and spend all day recording, from late morning to late hours at night. Vince was very purposeful; he knew what order he wanted to record everything. He didn’t want to write things out and make it sound mechanical; he liked it loose ... to play like we did on trio gigs.

Vince would bring in themes and ideas; he’d already been talking with John Scott Trotter or Lee [Mendelson], and he had a real plan. He’d bring in a storyboard on paper, and he knew the timings of everything; he was very well prepared every time. It could be improvised; he’d say, “Okay, we’ve got a cue here that’s about a minute and a half” or “This one is 17 seconds.” Sometimes Vince would say, “I dunno ... we need some mood music,” and he’d just start playing something! Of course, some of it was themes from other shows, and we’d do a new version of, say, “Linus and Lucy.”

[The music on the album] sounds fresher to me, because you don’t hear it in the show so much, because it’s designed to be a background; this way you can just listen to them. I’ve never had these tracks this way, and it’s so much fun.

I wonder where the time has gone, because I feel like the same person, particularly when I listen to this record. I just turned 80, but I have no sense of it (other than a doctor visit or two). This record pulls me back into the studio, with those players. They’re good, strong memories. You hear Vince’s voice in the studio. You hear him count it off, or say something, and that really makes you feel like you’re listening to tracks, and not a prepared album. That’s pretty fun.

I’d probably still be in the band, if Vince were still alive.

Like, wow.

I’d kill to be able to go back in time, and include that final line in my book.

********

On a related note...

As I explain in my liner notes — and in an amusing example of history repeating itself — much the way It Was a Short Summer, Charlie Brown began life as It Is a Short Summer, Charlie Brown, this special originally was to be called You’re Elected, Charlie Brown ... until the very last second. Wiser heads pointed out that a) Charlie Brown never wins anything; and b) Linus is the person campaigning, not good ol’ Chuck. Last-minute adjustments were made in such haste that the chalkboard title, as this special begins, has an afterthought “Not” inserted with a caret, and — listen carefully — the kid chorus still sings “You’re Elected, Charlie Brown.”

How “last minute” was this change made? Late enough to prevent being able to modify this promotional ad, which ran in TV Guide on October 28, 1972!

Thursday, February 15, 2024

Summer comes early this year!

Tuesday, October 24, 2023

Pass the drumstick!

Tuesday, October 11, 2022

Playing for Peanuts

Sunday afternoon was way too much fun.

Constant Companion and I were among the full house present at Santa Rosa’s Luther Burbank Center for the Arts this past Sunday, October 9, for the world premiere of Playing for Peanuts: The Music of Vince Guaraldi.

Jazz pianist David Benoit, well regarded as the primo torchbearer for Guaraldi’s Peanuts legacy, along with his trio — Roberto Vally, bass; and Dan Schnelle, drums — were joined by the impressively large Santa Rosa Symphony. (Honestly, I’m not quite sure how all those musicians fit onto the comparatively small stage.) The Symphony was directed by Francesco Lecce-Chong, although Michael Berkowitz earned the spotlight as Principal Pops Conductor (beginning his final season with the Symphony).

Berkowitz was an ideal choice as conductor; he’s almost as animated as Bill Melendez’s TV special renditions of Charlie Brown and his friends.

This ambitious project has been a collaborative effort, for the past couple of years, between Benoit, Sean Mendelson and Jason Mendelson. Designing, developing and fine-tuning these new orchestrations of Guaraldi’s music — all arranged by Benoit — kept all three occupied while they were sequestered by Covid.

Their approach was quite clever: blending Guaraldi’s iconic themes — along with equally delightful, but lesser-known score cues — into themed “medleys.” The long-term goal is to take these new orchestrations “on the road,” and also to make them available for orchestral units across the United States (and anywhere else in the world). For the most part, the medley sequencing is immaterial, as is the decision on how many to include in a given performance by an ensemble of any size. Two, three or four medleys could serve as one-third of an orchestral performance; alternatively, many could be blended to make a two-hour Peanuts Guaraldi extravaganza.

Sunday’s Santa Rosa performance, at slightly more than an hour, came somewhere in the middle.